Virtual Biomechanics Review #1

Our very first biomechanics review comes from a lovely young lady I know from teaching 4H camp. Obviously she isn’t our typical dressage entry, but I admire her for being brave enough to be our first review – thank you!

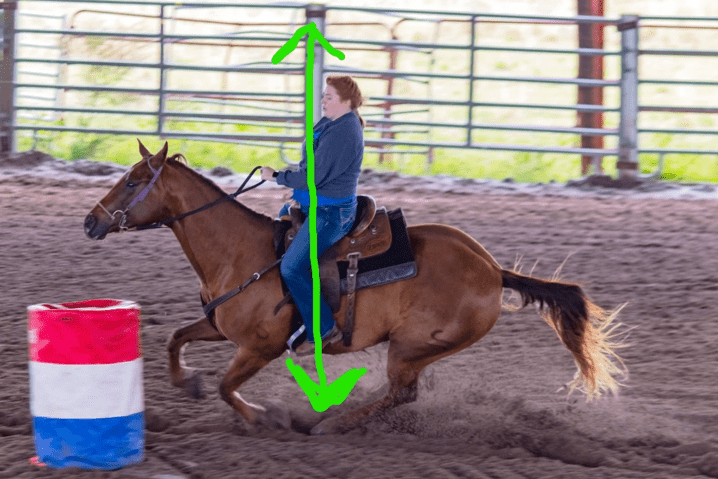

To help me with understanding what is going on in the picture at this moment, she said “During this time I was preparing to sit for our third barrel to turn. I cue him by applying inside leg pressure, sitting, and pulling up on the rein.” So here goes!

Please remember that this commentary is only about the rider’s biomechanics and how they can affect the horse more positively/negatively; I do not have a deep working knowledge of barrel racing as a discipline, so please take the advice in the vein it is given.*

The Line Up

One of the first things I look for in a rider is her “line up,” or how stacked she is in her own balance. For a rider to be in control of their own body weight, they should be (almost always) in a balance that if I were to pull the horse magically out from underneath them, they would land on their feet.

Coming into this barrel, she is behind this line up with her upper body; she may even be doing the historically advised “lean back” on purpose! Unfortunately, by doing this, her balance now becomes the problem of her horse — as she is approaching the last barrel, she is pushing his weight onto his shoulders by leaning back. The need to “pull up on the rein” comes as a by-product of the balance shift, as she feels the horse shift under her onto his shoulders, making it difficult to make the turn without some intervention of the rein.

Passive Resistance

As anyone who has seen barrel racing knows, there is a huge amount of speed and compression taking place alternately. These two forces act on the rider’s body, per the laws of physics, and cause riders to get moved by their forces. The more the rider gets moved by physics (see Newton’s Third Law for clarity), the more the horse will need to adjust underneath them to maintain balance for both; this phenomenon can cause valuable 10ths of seconds to be lost on the clock.

So how do we prevent this? The idea of passive resistance comes into play.

For an interactive example, press the palms of your hands together in front of your chest, gently. Imagine that the energetic resistance at this moment is a 1 out of 10. Gradually increase the pressure of your palms against each other, so that you are working harder and harder to push your hands together, until you can’t push any harder…this is a 10 (for you). If someone was watching you do this, they would see very little movement on the outside, as each hand is pushing equally. You would appear to be doing nothing more, but you know that you are pushing with all your might.

This kind of exertion is called isometric, and it is the basis of passive resistance. Isometric, for our purposes, can be defined as “An isometric exercise is a form of exercise involving the static contraction of a muscle without any visible movement in the angle of the joint.”

To get back to our rider, we can simply state that this rider did not follow Newton’s Third Law and was moved back by the impulsion created from the horse’s hind leg. Her lack of ability to match forces then caused a compensatory balance change in the horse, which caused it to lean into the turn, against which she raised her rein to try to rebalance him.

So how do we fix it? The answer will not be what you would expect it to be, and that is why rider biomechanics is both fun and confounding!

Bucking the System

In many of the riding disciplines I work with, rider biomechanics bucks the system, telling people to “lean forward” where they have always been told to “lean back”, or “attach your thighs” when the common word is to “let your thighs drape”.

For this rider to more effectively “stay with the horse”, we need her to close her upper body more towards the horse’s neck, starting from her hip angle. This would feel tremendously foreign, almost as if she were going to fall off the front of the horse. She would need to be more attached with her whole length of thigh on either side, to help maintain this position, and not just leaning into the inside thigh.

It would take a lot of passive resistance in the front of her body to match the force against her, namely speed, for her to stay lined up in her body while approaching the barrel. I would ultimately like her body to be more on the green line, as diagrammed below:

What will this do for her ultimately?

It will keep her more over her horse’s center of gravity, allowing her to continue to be in charge of her own weight, which allows the horse to move better underneath her, rather than having to absorb the shift in her body. This should, over time and practice, help them come to the barrel better, get around it quicker, and cut down on some time on the clock!

Have a biomechanics question?

Email me a picture of you and your horse from the side with a little description of what you were doing at that moment. I’ll be happy to review it (and redact your name). Until then, keep your eye on horizon and don’t forget to pet your horse!